Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

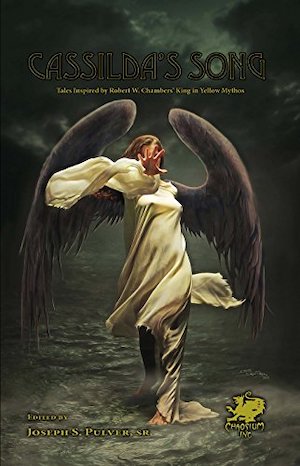

This week, we cover E. Catherine Tobler’s “She Will Be Raised a Queen,” first published in Joseph S. Pulver Sr.’s Cassilda’s Song: Tales Inspired by Robert W. Chambers’ King in Yellow Mythos in 2015. Spoilers ahead!

“The house with its straight walls and narrow entries holds no consolation for me; everything closes a person away from the world, and no matter how ruined and desolate since the plagues that carried everything away, I miss the skies and the crumble of ground between my toes.”

The narrator has no name, though of course she has a name, and a song, but for the three men who find her, What are you is the constant question. As she’ll eventually tell one, “he does not want to know, because he does not care.”

The men pull her from “the sulfur-yellow waters of the nameless lake.” Ridiculous to call her a mermaid, Ambrose Kowal says, for she has two legs—strong ones with which she kicks Nicholas when they try “spreading her wide for study.” Frederick, who’s told the others a tale of black stars in a black sky, calls her “a queen, a queen of Carcosa,” and says she will do.

They guide her out of a world ruined by plagues and fouled by volcanic stench into the city they mean to rebuild, seat of a new “Empire.” Mayor Ambrose has a house of fire-blackened stone, but inside it’s tidy, with warm drawing rooms, cakes and ale, and bedrooms outfitted with “soft linens.” Narrator prefers to curl in her room’s iron tub, though its faucet water doesn’t satisfy her cravings and servants disapprove of her behavior.

She roams the house at will. Ambrose’s wife, Lady Kowal, shies away from her. Cousin Angelica is friendlier. She tells narrator that the room at the house’s apex is only storage for discarded items. The “transcendent” portrait cached there represents The Violet, a woman whom “Pascal” so loved that “he filled her with a child” while neglecting his wife.

The room’s yellow wallpaper is tattered except in corners, where narrator can make out roads, rivers, places yet untraveled. At night she unbuttons her skin and enters the wallpaper world, where none need “regard [her] as anything other than what [she is]… something wholly other and pure.” Her feet know the way past the lake of Hali to the “arched and twilight shadows” where the tatter-cloaked Other stands, faceless though she touches a face, mouthless though she presses her mouth to its, to be flooded with cold, sharp nothingness. Much shall be done, says a voice that vibrates in her bones. “Thy will be done,” she promises.

Back in the yellow room, she re-dons her skin. Black stars line the seam of her arm like buttons, and she breathes with the breath of the Other.

At breakfast Angelica pries apart raspberries. Ambrose says they’re building an Empire, but she says nothing changes. Nights are endless; she wakes feeling she spent the whole time wandering. She wants narrator to take her to the yellow lake, but narrator knows it would devour her. Yet Angelica’s eyes are the color of the black stars.

Ambrose enters. He wants narrator to “come to [him],” telling no one, as “there are matters between [them]” which must be laid “plain. Bare. If [she is] such a queen.” Her response is to send a “gentle cloud” of black stars to swallow Ambrose—she wishes they would tear him open, but “the darkness knows patience” and withdraws. Ambrose slumps to the table. Leaving, narrator brushes past Lady Kowal and feels an unnatural coldness.

Back in the storeroom, among disordered boxes, Nicholas kneels entranced. Narrator takes him into the wallpaper-world. As the waters of Hali suck off their other-dimensional skins, Nicholas screams. He’s believed there “was only ever a king…aging and tattered, and all have gone mad.” They traverse a wood under “the twin suns,” and Nicholas is pulled into its mossy ground and devoured, his “seeds” scattering. The narrator’s king embraces her with “vaporous arms” and shows her the hole in the world where everything spirals inward as black stars.

Come morning, in the dining room, narrator takes Angelica’s shaking hands. They memory-travel to the yellow lake, where Angelica’s being drawn from the water by the three “empire-builders.” Ambrose promises he’ll heal her sick body so she can carry a child who may “draw down the light of Hyades.” They travel to a yellow room with intact paper, where Angelica lies on a gold-draped couch while three pairs of hands part her “like a raspberry.” From the couch she’s lifted into the color yellow itself, “good and glorious.” One day she may need the poisonous apple seeds she collects there. But now she carries Frederick’s child…or the child of the three men in collusion.

That night Ambrose awaits narrator in the restored yellow room. She unbuttons her skin and pulls him where he thinks he wants to go. Later, chair-confined, his wife freed, he’ll be unable to describe his experience. Before the faceless king, he kneels in horror; reviled by the narrator, he turns angry “in the way of men.” She floods him with black stars until he collapses at the king’s feet.

Later she tells Frederick she’s removed Lady Kowal and Angelica to a safe place, one where Angelica can deliver a child who “will wear no mask.” Transported to the wallpaper-world, he begs to know what she is. Enveloped in her king’s tatters, she cuts him from thigh to throat and fills him with the “awful truth he has always known.” Like Ambrose, he’ll bear the mark of black stars the rest of his life: a man who aspired to rule an Empire, who dared look on the king’s unface, who tried to own bodies not his own.

He’ll dream of water, the “black-star ocean,” and when he glimpses the child flitting by, he’ll call her mermaid. But she’s no mermaid—“she will be raised a queen.”

What’s Cyclopean: Glorious language this week, from the “pewter sky” to Lady Kowal’s “throat drawn in tight lines that would allow no words passage” to a room’s corner “where wall meets wall in a soft kiss”.

The Degenerate Dutch: Frederick can’t stop making lascivious comments about Cassilda, and ultimately gets about what you’d expect for his “explorations”.

Weirdbuilding: To Cassilda, the British house is “terrible in its geometries” except for the crowning room that is—of course—yellow.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Nicholas doubts until the last minute that Carcosa ever had a queen—he believes there were only ever tattered kings that aged and went made.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Hello, Cassilda. Cassilda, that is you, isn’t it? I think so, albeit Cassilda by implication, both her name and the name of her rag-tattered king masked throughout the story. This whole story masks sideways implications in rich language—and occasionally unmasks them. Appropriate, for lost Carcosa.

What does it mean for Carcosa to be lost? After all, there are already people there, or entities at least. Here, Carcosa seems discovered, as inhabited lands so often were, by gentlemen determined to make a proper, rational life on a foundation of afternoon tea and tidy cobblestone houses. It’s not quite clear how they got there, or when they got there, or why they decided that this was a good place to set up housekeeping—or whether they really had a choice. Perhaps they’re stranded and trying to carry on, or perhaps Carcosa is a source of power and riches that might be of use in an empire equally lost. The city holds a “virtuous civilization” that is trying to “recover and return to the world they had once known,” but it’s not clear whether that means “civilizing” the Carcosan landscape in the image of a desolated Earth, or restoring Carcosa to a glory they themselves remember. They describe the city as a “settlement” and vote on renaming Lake Hali, but are also trying to create “what could not be destroyed as all that had been before”. And Ambrose lost all that he loved to pieces and plagues a long time ago.

Perhaps Carcosa isn’t the only place that’s suffering. Perhaps there are problems on Earth that make flight worthwhile. Assuming the city is on Carcosa and not on Earth itself. Assuming Earth and Carcosa are different places at all.

Wherever we are, it’s been doing poorly for a while. The water is sulphureous, the air plague-ridden. Darkness that seeps deep into the stones and cannot be scrubbed away. Even Cassilda, who thrives flamingo-like in the lake’s poisonous waters, describes loss and destruction.

It’s not surprising, in a King in Yellow story, that past and present and self all seem to shift with every paragraph. Cassilda looks at first for selkie skins along the bank, not knowing her own nature—then later finds black stars like buttons that allow her to shed skin after all. Then she finds those same stars on others, and the same yearnings and vacillations. Angelica vivisects raspberries, looking for something, baring desires to Cassilda that she hides from the men. The men pray and desire and plan, and become vulnerable to being broken down and remade and refilled. The King’s will is done, even though will is an illusion. Black stars seep into everything. Time breaks down, not the denial of time that is Empire but the boundary between past and present.

Angelica is herself also a child of the lake, pulled out to birth… something. A child who will wear no mask. (No mask? No mask!) A child who will be raised a queen. Whatever that means; everything that means. Raised: lifted, out from a yellow lake that strips flesh. Raised: summoned, across dimensions or world or times, bringing power that the summoners don’t understand and deals they didn’t mean to make. Raised: reared from childhood to adulthood, with goals that those doing the rearing have only limited control over.

I am quite certain that I don’t understand this story, but I’m also not sure it would be safe to do so. Better to let it flow through and away, like a river of black stars.

Anne’s Commentary

I don’t normally go in for conspiracy theories, but after reading “She Will Be Raised a Queen” and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s famous story, I’m considering a campaign to have yellow wallpaper banned in all fifty states. Some yellow wallcoverings may be innocuous, all daisies and daffodils and ducklings. However: Do you want to risk your home decor being part of a pernicious plot to drive you bonkers? Or worse: A gateway to alien dimensions, say, Carcosa?

Please, consider contacting your representatives about this issue. Mine haven’t gotten back to me yet. Which makes me wonder what’s on their bedroom walls.

Now that I’ve done my civic duty, let’s consider this world Tobler’s created. It raises many questions it never answers, or wants to answer, leaving readers to puzzle the mysteries out for themselves. Alternatively, readers can just go with the dreamlike flow of the narrative, accepting that SOMETHING BAD HAS HAPPENED HERE and drifting onward. Me, I’m dog-paddling against the seductive current. What is the SOMETHING BAD, I want to know, and where’s the HERE it happens in?

Does “Raised a Queen” take place on a future Earth, or on an alternate history Earth with an earlier timeframe? Details of clothing and domestic arrangements suggest a Victorian/Edwardian setting, as do the dialogue, manners and behavior. Another possibility is that survivors of SOMETHING BAD have reverted to the age of empire, c. 1850 to 1914, as if to a more halcyon time or to a civilization they consider better able to cope with the catastrophe. Or the setting may pay homage to the 1895 publication of Chambers’s “King in Yellow.”

Many are the existential crises our planet might face. They range from the astronomical (asteroids, gamma ray bursts, solar flares) to the manmade (climate change, AI or other technologies gone “rogue,” nuclear war.) Natural phenomena like pandemics or supervolcanoes could also get us. Tobler’s world has suffered multiple whammies. Volcanic mayhem has apparently created sulfurous lakes, crusted ground, and fire-blackened ruins. The air is “plague-ridden.” Outside the walled city under reclamation, all is “poisoned,” “ruined,” “sickened.” The narrator’s “rescuers” suspect that monsters such as mermaids and selkies populate the wilderness and search the lakeshore for a bestial skin the narrator might have shed to mimic humanity.

Their concern may be more than trauma-induced superstition: The narrator is able to shed and resume her skin to adapt to different environments. The sheddable skin is her human disguise. “Unbuttoning” it, she emerges as something neither selkie nor mermaid nor woman; she becomes “wholly other and pure,” worthy of passing into Carcosa and the embrace of the ultimate Other, her king.

The narrator has no name she ever speaks, but she does have one, and it has its own song, which is Cassilda’s. Another existential catastrophe would be outside intervention by extraterrestrials. One might extend the definition of extraterrestrial to supernatural or even divine entities. Say, if one were an apocalyptic cultist, or Frederick, who seems to know a lot about the King and Carcosa. The yellow lake in the “sickened” world, from which the empire-builders haul their broodmares, seems to mirror Carcosa’s lake of Hali, which itself mirrors the black stars and twin suns of the King’s realm.

Could a Carcosan invasion be the source of the plagues ravaging Tobler’s world? If so, did the King send them—or—

Did those empire-builders or some occultist predecessors call down the plagues? It’s clear they’re up to occult funny business, what with their gold-draped couches and that “transcendent” portrait of The Violet serving as their version of a Madonna, a Savior’s Mother. According to Ambrose, the savior would be “a creature that might reach across worlds, might draw down the light of the Hyades and make it shine once more.”

Might make the empire-builders’ world great again?

It’s an ambition the narrator finds overweening. Her response is “But oh my King we never ceased shining—what do they mean to do?” During her first visit to the Other, it tells her “Much shall be done,” but not, I take it, by the empire-builders. “Thy will be done” is the narrator’s vow. That she keeps it by rescuing her sister “Madonnas” and destroying their defilers indicates that the King’s will was never to let the light of his Hyades shine on them.

Tobler has deftly described Lady Kowal as wearing blue “for the Mother.” Christian iconography drapes Mary Mother of God in blue, but Lady Kowal may be that “proper ladywife” not loved enough to bear a child. If so, no wonder “her eyes ran with venom” when the narrator pressed her about the men’s doings. Angelica is the favored one, a closer sister to the narrator in the black-star color of her eyes and the echo of black stars in the pulse at her throat. Her child, the narrator senses, has been engendered by no one man but by the three “in collusion,” seeking to impregnate her magically with a future queen of Carcosa.

Herself the reigning queen of Carcosa, the narrator will make a proper godmother for that child, don’t you think?

I do.

Next week, join us for final confrontations with fiends and the past in Chapter 13 of Hilary Mantel’s Beyond Black.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of A Half-Built Garden and the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon and on Mastodon as [email protected], and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.